Markets

The Controversy Around Stock Buybacks Explained

The Controversy Around Stock Buybacks Explained

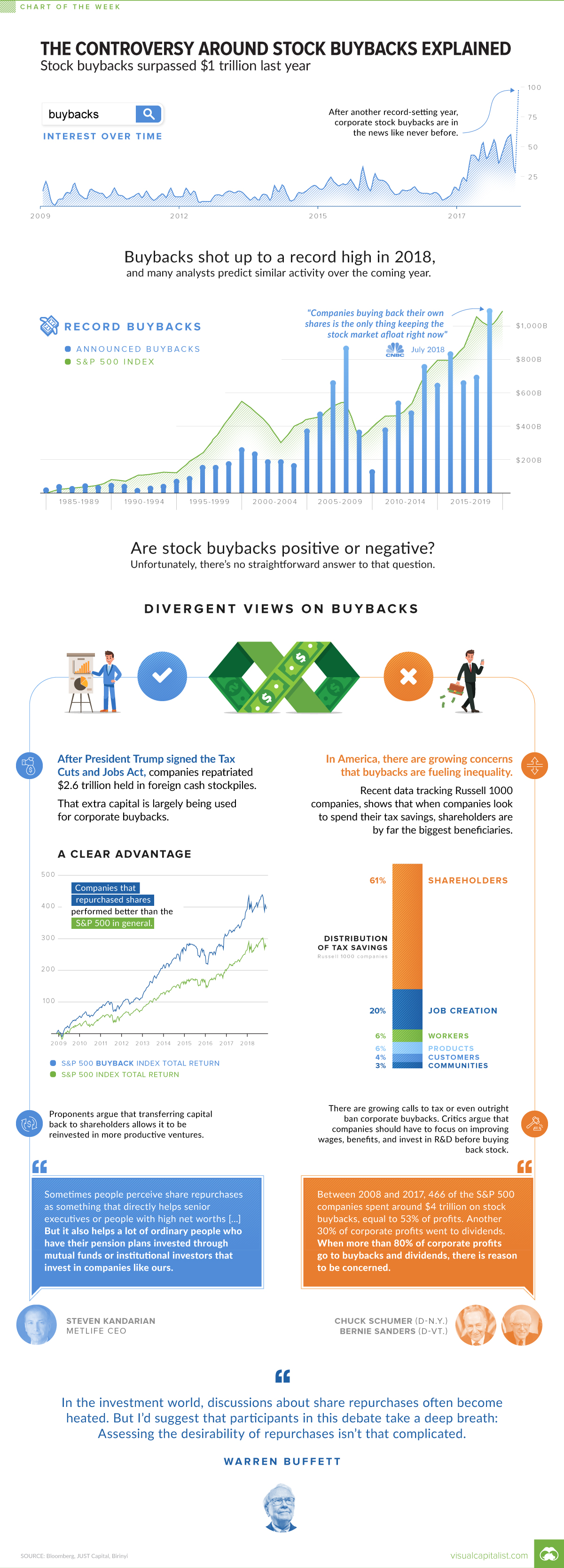

At face value, the notion of companies buying back shares in their own stock may seem pretty benign.

But as soon as trillions of dollars are being poured into any single cause – regardless of how innocuous it may sound – there is always the potential to make a lightning rod for controversy.

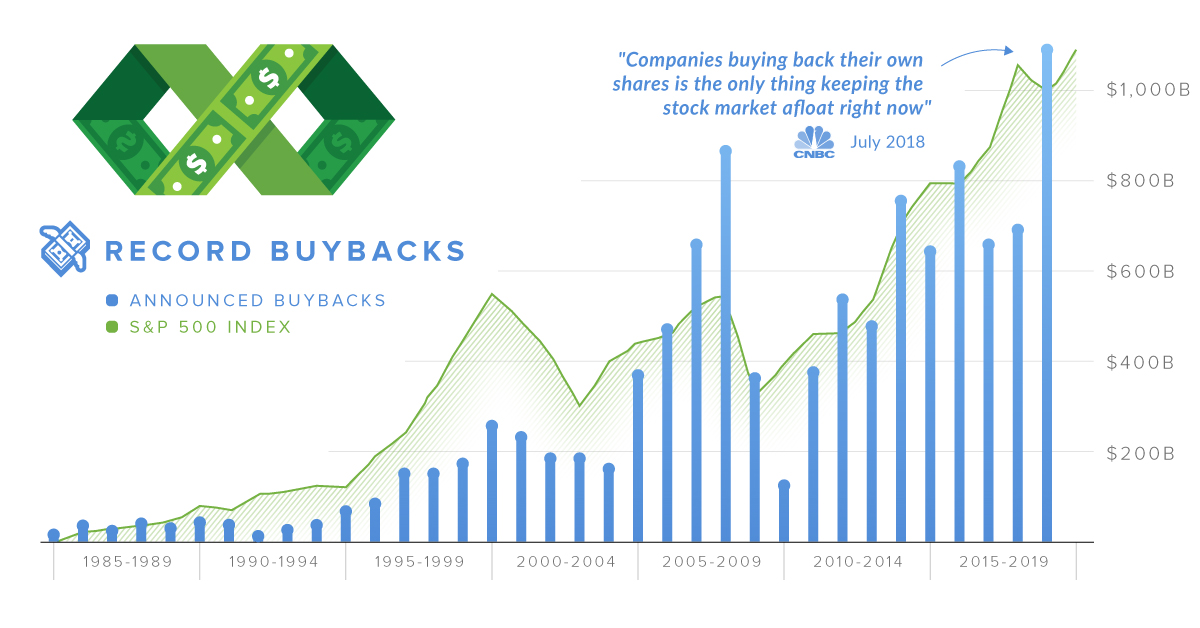

With stock buybacks totaling $1.1 trillion in 2018, they’re at the center of discussion more than ever before.

What are Stock Buybacks?

When publicly-traded companies want to return money to shareholders, they generally have two options.

The first is to declare a dividend, but the other is to repurchase its own shares on the open market.

Although it seems meta, stock buybacks are a way for companies to re-invest in themselves. Each buyback decreases the amount of shares outstanding, with the company re-absorbing the portion of ownership that was previously distributed among investors.

In other words, buybacks are somewhat analogous to buying out a business partner – they allow the remaining partners to own a higher share of the company.

Pro vs. Con

With the amount of stock buybacks rising to historic highs, they have been front and center in 2019. Here are what proponents and opponents are arguing about.

Pro Case:

Proponents of buybacks say that if they are done rationally, buybacks (like dividends) are just another way to return cash to shareholders. Stock prices for companies that have bought back shares are also higher, in general, than other companies on major indices like the S&P 500.

Con Case:

Opponents of stock buybacks say that they increase inequality, and that executives make short-term oriented decisions around buybacks that allow them to maximize personal gain. In other words, when a company probably should be investing in its people or its business, the company is instead giving money back to the wealthy owners – and only they benefit.

The Bottom Line

While both sides make a compelling argument for different reasons, the only real way to evaluate stock buybacks is based on the merits of individual companies.

If the company is returning money to shareholders because it is the best allocation of capital, then it can make perfect sense. If the company is doing it at the expense of growing its business and the wages of employees, one can see why stock buybacks may rub people the wrong way.

Markets

U.S. Debt Interest Payments Reach $1 Trillion

U.S. debt interest payments have surged past the $1 trillion dollar mark, amid high interest rates and an ever-expanding debt burden.

U.S. Debt Interest Payments Reach $1 Trillion

This was originally posted on our Voronoi app. Download the app for free on iOS or Android and discover incredible data-driven charts from a variety of trusted sources.

The cost of paying for America’s national debt crossed the $1 trillion dollar mark in 2023, driven by high interest rates and a record $34 trillion mountain of debt.

Over the last decade, U.S. debt interest payments have more than doubled amid vast government spending during the pandemic crisis. As debt payments continue to soar, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) reported that debt servicing costs surpassed defense spending for the first time ever this year.

This graphic shows the sharp rise in U.S. debt payments, based on data from the Federal Reserve.

A $1 Trillion Interest Bill, and Growing

Below, we show how U.S. debt interest payments have risen at a faster pace than at another time in modern history:

| Date | Interest Payments | U.S. National Debt |

|---|---|---|

| 2023 | $1.0T | $34.0T |

| 2022 | $830B | $31.4T |

| 2021 | $612B | $29.6T |

| 2020 | $518B | $27.7T |

| 2019 | $564B | $23.2T |

| 2018 | $571B | $22.0T |

| 2017 | $493B | $20.5T |

| 2016 | $460B | $20.0T |

| 2015 | $435B | $18.9T |

| 2014 | $442B | $18.1T |

| 2013 | $425B | $17.2T |

| 2012 | $417B | $16.4T |

| 2011 | $433B | $15.2T |

| 2010 | $400B | $14.0T |

| 2009 | $354B | $12.3T |

| 2008 | $380B | $10.7T |

| 2007 | $414B | $9.2T |

| 2006 | $387B | $8.7T |

| 2005 | $355B | $8.2T |

| 2004 | $318B | $7.6T |

| 2003 | $294B | $7.0T |

| 2002 | $298B | $6.4T |

| 2001 | $318B | $5.9T |

| 2000 | $353B | $5.7T |

| 1999 | $353B | $5.8T |

| 1998 | $360B | $5.6T |

| 1997 | $368B | $5.5T |

| 1996 | $362B | $5.3T |

| 1995 | $357B | $5.0T |

| 1994 | $334B | $4.8T |

| 1993 | $311B | $4.5T |

| 1992 | $306B | $4.2T |

| 1991 | $308B | $3.8T |

| 1990 | $298B | $3.4T |

| 1989 | $275B | $3.0T |

| 1988 | $254B | $2.7T |

| 1987 | $240B | $2.4T |

| 1986 | $225B | $2.2T |

| 1985 | $219B | $1.9T |

| 1984 | $205B | $1.7T |

| 1983 | $176B | $1.4T |

| 1982 | $157B | $1.2T |

| 1981 | $142B | $1.0T |

| 1980 | $113B | $930.2B |

| 1979 | $96B | $845.1B |

| 1978 | $84B | $789.2B |

| 1977 | $69B | $718.9B |

| 1976 | $61B | $653.5B |

| 1975 | $55B | $576.6B |

| 1974 | $50B | $492.7B |

| 1973 | $45B | $469.1B |

| 1972 | $39B | $448.5B |

| 1971 | $36B | $424.1B |

| 1970 | $35B | $389.2B |

| 1969 | $30B | $368.2B |

| 1968 | $25B | $358.0B |

| 1967 | $23B | $344.7B |

| 1966 | $21B | $329.3B |

Interest payments represent seasonally adjusted annual rate at the end of Q4.

At current rates, the U.S. national debt is growing by a remarkable $1 trillion about every 100 days, equal to roughly $3.6 trillion per year.

As the national debt has ballooned, debt payments even exceeded Medicaid outlays in 2023—one of the government’s largest expenditures. On average, the U.S. spent more than $2 billion per day on interest costs last year. Going further, the U.S. government is projected to spend a historic $12.4 trillion on interest payments over the next decade, averaging about $37,100 per American.

Exacerbating matters is that the U.S. is running a steep deficit, which stood at $1.1 trillion for the first six months of fiscal 2024. This has accelerated due to the 43% increase in debt servicing costs along with a $31 billion dollar increase in defense spending from a year earlier. Additionally, a $30 billion increase in funding for the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation in light of the regional banking crisis last year was a major contributor to the deficit increase.

Overall, the CBO forecasts that roughly 75% of the federal deficit’s increase will be due to interest costs by 2034.

-

Markets2 weeks ago

Markets2 weeks agoVisualizing America’s Shortage of Affordable Homes

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoRanked: Semiconductor Companies by Industry Revenue Share

-

Money1 week ago

Money1 week agoWhich States Have the Highest Minimum Wage in America?

-

Real Estate1 week ago

Real Estate1 week agoRanked: The Most Valuable Housing Markets in America

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoCharted: Big Four Market Share by S&P 500 Audits

-

AI2 weeks ago

AI2 weeks agoThe Stock Performance of U.S. Chipmakers So Far in 2024

-

Misc2 weeks ago

Misc2 weeks agoAlmost Every EV Stock is Down After Q1 2024

-

Money2 weeks ago

Money2 weeks agoWhere Does One U.S. Tax Dollar Go?